A talk by MARIANA ISA and MAGANJEET KAUR

Nowadays Kuala Lumpur appears to be a modern city with shiny high-rise buildings and wide roads, one upon the other, along with day and night bustling activities.

In between all these new urban constructions the historical buildings of the city are in steep decline. Therefore, among all these changes the only traces left to guide through Kuala Lumpur’s past will be the street names. As they also have undergone changes during the past 100 years, the project of Mariana Isa and Maganjeet Kaur to publish Kuala Lumpur’s street names is particularly important.

These two independent researchers have collected the city’s street names and explained their meaning and history in their guidebook, published in 2015. But the research on Kuala Lumpur’s street names isn’t only a personal interest of these two heritage enthusiasts. Coming from a university background, with Mariana having a MSc in Conservation of Historical Buildings from the University of Bath/England and Maganjeet holding an MSc in Information Technology of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, they are interested in providing research-based services to organisations and individuals regarding the local history and heritage. To cater for this concern, they founded the Heritage Output Lab. MCG members and friends had the great opportunity of getting a glimpse of the short but diverse history of Malaysia’s Capital on the topic of Kuala Lumpur’s street names at first hand from these two experts.

To keep it clear and comprehensible for the mixed audience of veterans and newcomers, Maganjeet began their talk with a historical overview before she introduced the three old quarters which formed the historical city center. She started with the Chinese Quarter, which covers today roughly the area between Masjid Jamek and Petaling Street, and continued explaining the historical Merdeka Area, before Mariana concluded the talk with the Malay Quarter, which was located around Ampang Street (Leboh Ampang) and High Street (JalanTun H S Lee).

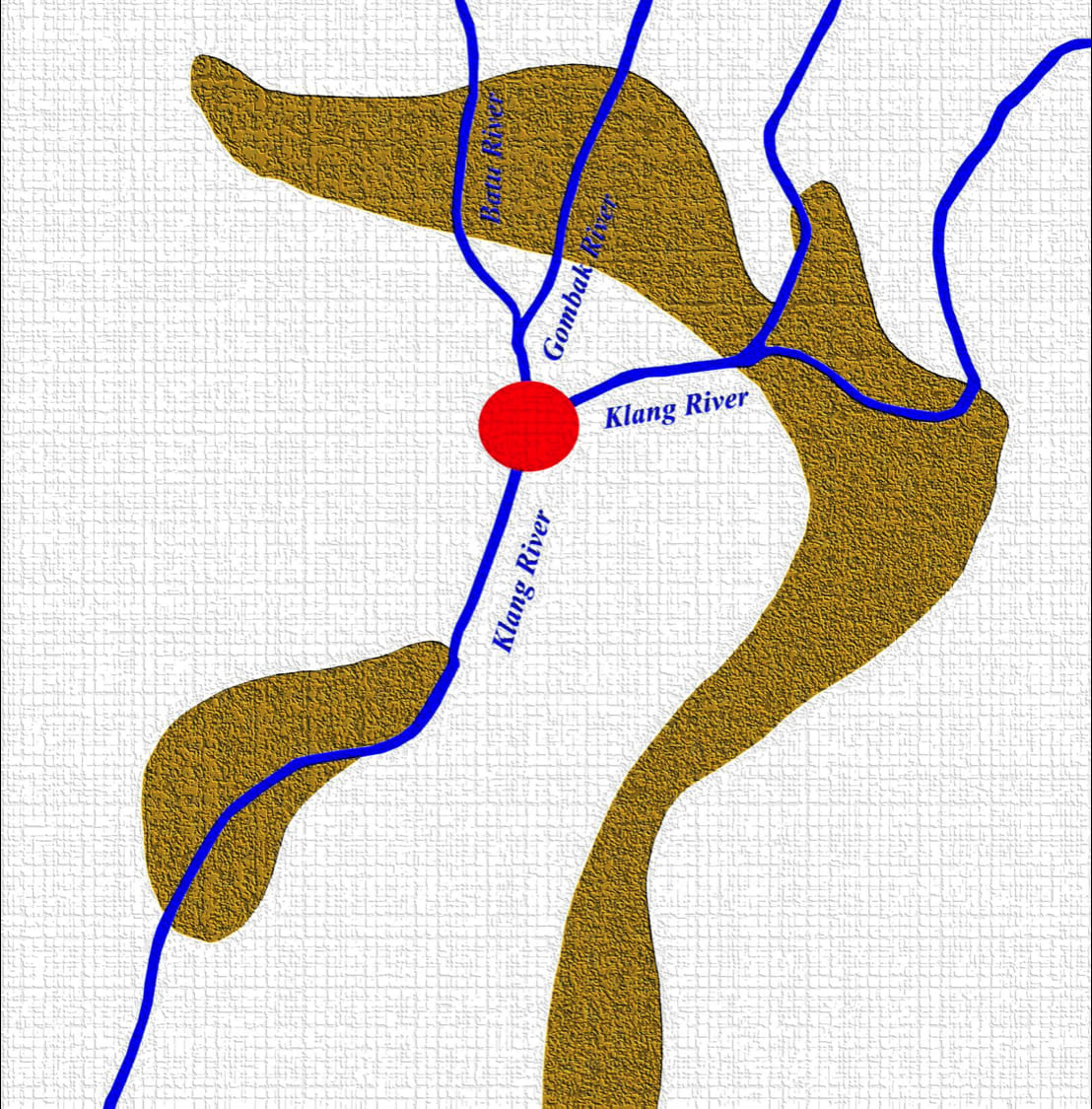

Most of the settlements in the world were created along a river, so does Kuala Lumpur owe its existence to the confluence of the Rivers Klang and Gombak, which reach the Straight of Malaka as Klang River in Port Klang. The boats from Klang to Kuala Lumpur couldn’t get further than the confluence and already up to this point the journey took three days and was difficult. But the effort was made to reach the tin belt situated around Kuala Lumpur, whereas the main mines were in the North and East of the Town.

Officially mining around Kuala Lumpur started in 1818 and reached, by 1859, an output high enough for export. That was the moment when Kuala Lumpur arose as a trading point for the tin to be shipped to Klang and from there the boats returned loaded with goods for the mine workers. The rise of Kuala Lumpur came to a halt during the Selangor Civil War, but picked up after 1874 fabulously. This was largely due to Yap Ah Loy’s perseverance to rebuild the town after the Civil War.

Yap Ah Loy, who came from Guangdong province in China, started his career as a trader in Seremban. Attracted by the promise of wealth, Yap moved to Kuala Lumpur in 1862 and worked for the Kapitan Cina, Liu Ngim Kong. After the Civil War Yap was the largest tin mining entrepreneur in Kuala Lumpur.

When the British decided in 1880 to move the capital from Klang to Kuala Lumpur the access to the city was enhanced by building roads and finally a railway over the years. In 1896 Kuala Lumpur became the capital of FMS.

In these early days “when rivers functioned as the primary means of transportation, the streets of Kuala Lumpur were merely secondary and tertiary arterials. These streets began as dirt paths – clearances cutting through tropical forests and jungles. The paths would be covered with coconut leaves during the rainy season to avoid the inconvenience of a muddy track. Major routes were constructed up to a width of 18 feet (5.5 metres), wide enough to allow bullock carts to pass through.” (Isa/Kaur, Street names, p.6) So, not surprisingly it isn’t an easy task to trace back the street names in the young Capital because the written records are limited. But there are hints that the different groups of early settlers had names for the streets in their own language, that’s why there are different names for the same street. These early names given by ordinary people are assumed to have reflected local traditions, lifestyle or events. Under British administration the local names were written off or translated and unfortunately the names of the pre-British period gradually disappeared without a trace.

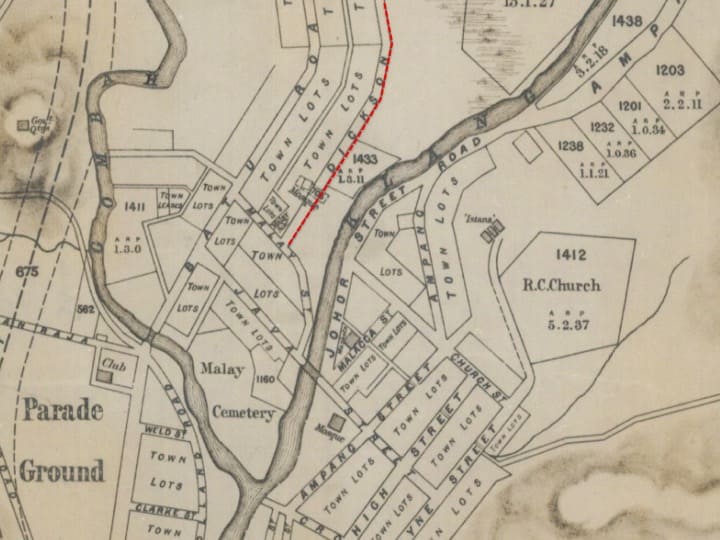

The early manner of street naming in the city was rather simplistic and the names served primarily as directional indicators, so e.g. the name Ipoh Road was given to the road that led to Ipoh. Back then the same names had semantic content that reflected topographical features, like names of mountains, rivers and trees. Nowadays hardly anyone knows that e.g. ipoh is also a name of a tree (epu tree). Commemorative names were introduced by the British, like Dickson Street (Jalan Masjid India). Yap Ah Loy Street appears to be the only one named after a non-European or Eurasian that can be found on the 1889 map of Kuala Lumpur and it is the only name from this map that has lasted till today.

The heart of the new town was the confluence from where the different communities spread to create their own quarters. The Chinese built their houses south of the confluence, north of it was the Malay Quarter and West of it lived the British. An exemption of this pattern is Batu Road (Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman), which was one of the earliest tracks in Kuala Lumpur leading to Batu village in the North and became the main thoroughfare of the city. A mix of local notables had their residences there, among them were Sultan Suleiman, Raja Laut and Loke Yew, whose mansion has resisted development.

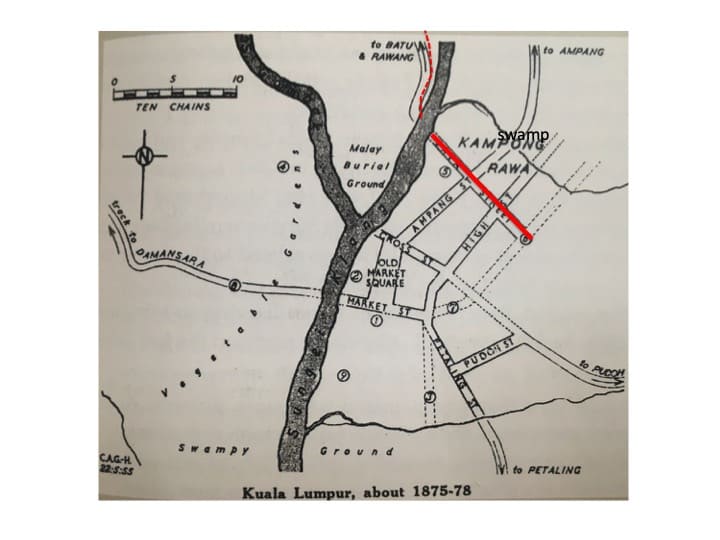

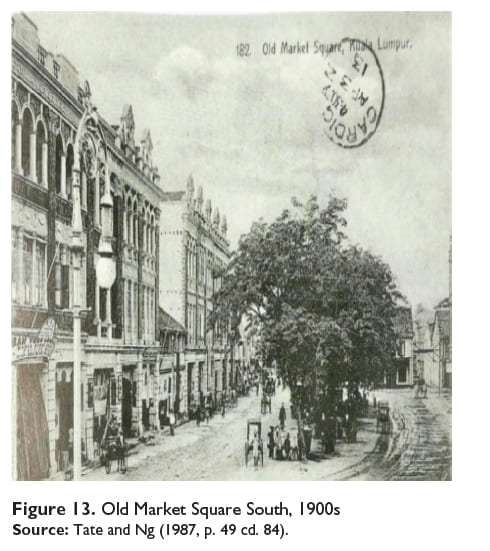

The old Chinese Quarter’s main center of activities was the area bounded by Market Street (Leboh Pasar Besar), Cross Street (Jalan Tun Tan Siew Sin) and High Street (JalanTun H S Lee). It was there, where the heavy boats couldn’t go further and it was probably the first quarter to be rebuilt after the Civil War.

The open space in front of Market Street became the first town center, from where the streets were built to link the center with the outlying tin mines and vegetable gardens.

One of the earliest roads in this quarter was Petaling Street, a road which led to the tin mines of Petaling. The name petaling originates from a local tree which is exploited for its timber to make houses because it is termite-resistant. To the Chinese the street is known as “Chee Cheong Kai” (= tapioca mill street). This unofficial name gives a hint to Yap Ah Loy’s tapioca factory here.

Initially Market Street ended at the East bank of Klang River. It was after 1880 when the British moved the capital to Kuala Lumpur and the government offices and residences were built on the West bank of the Klang River that the fragile wooden bridge was replaced by an iron one.

After Kuala Lumpur became the Capital of FMS, the British constructed their government quarter in the Merdeka Area and it was Sir Frank Swettenham as Resident-General (1886-1901), who laid the foundations of modern Kuala Lumpur.

First he embarked on a major clean-up of the town to provide more hygienic conditions as well as rebuilding houses and buildings in brick. By 1889 all houses were made of brick. He established a plan for the town including places of public interest, like hospitals or the railway station. Bridle roads, permanent bridges and a railway network were developed.

North of the confluence sprawled the Malay Quarter of Kampung Rawa which was connected with the heart of the city at the Old Market Square by Ampang Street (Leboh Ampang), an approach route to the village of Ampang. The street with its rows of Chinese shop houses crossed Java Street (Jalan Tun Perak) which formed the boundary between the Malay and Chinese Quarters. The name implies a concentration of Javanese traders.

Along the road the government built the Mughal-inspired Masjid Jamek. Subsequently Java Street became a shopping haven with the opening of department stores. North of Java Street, the Malay Agricultural Settlements were established in 1899 which secured the food supply for the city.

Are you now interested in more fascinating insights into the City’s past or do you want to explore your neighbourhood? Then you can browse the Guidebook of:

Mariana Isa and Maganjeet Kaur, Kuala Lumpur Street Names. A guide to their Meanings and Histories, Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2015.

Text: Birgit Groh

Photos and maps: Mariana Isa / Maganjeet Kaur