15th November, 2023

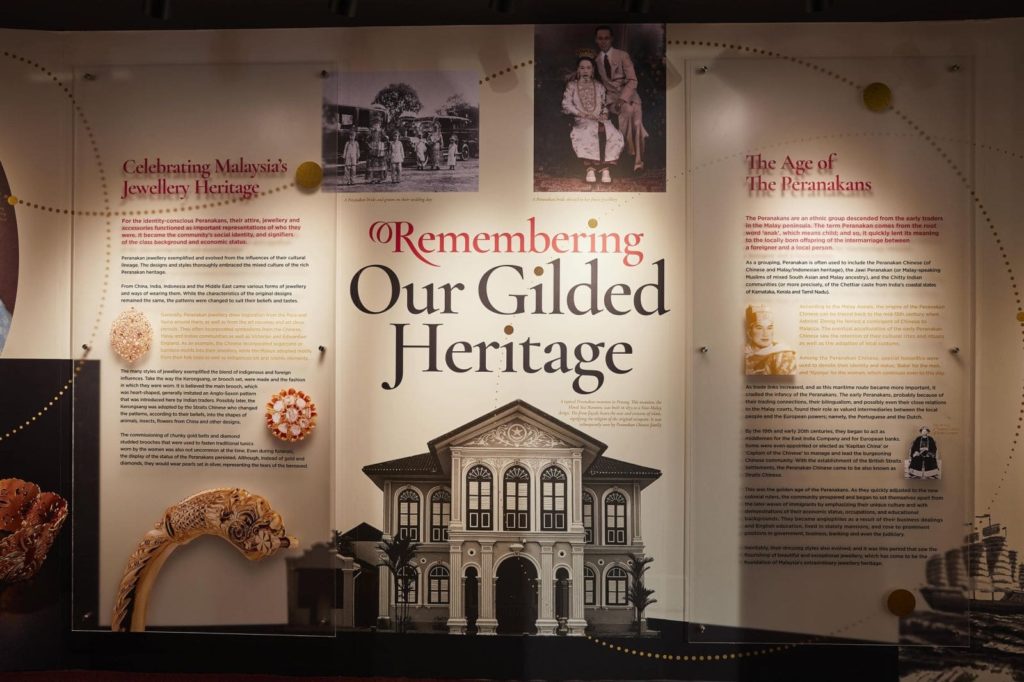

Imagine going to a gold shop where you are surrounded with the most inviting display of glittering gold rings, bracelets, necklaces, pendants and brooches, all dazzling and sparkling, but nothing is for sale. On Wednesday, November 15th, MCG organized an outing to Harta Heritage Jewelry Museum, a new gallery featuring Malaysian heritage jewelry set up by Habib Jewels. Our capable guide was Joe Lam, who is with the public relations department of Habib Jewels. He explained that the magnificent private collection on display consists of over 800 pieces that the family has collected over a period that reflects Malaysia’s age. Although the collection was started 60 to 70 years ago, the pieces were created several hundred years ago in some cases. The display focuses on Malaysia’s Peranakan heritage; Peranakan Chinese, Peranakan Jawi (the Arabs) and Peranakan Chitty (the Indians). The emphasis is on Malaysia’s multi-racial and multi-cultural identity revealed through a plethora of rich motifs and symbols in works of gold.

The Peranakans (people born locally of mixed heritage, usually Chinese and Malay, who can trace their origins back to 15th-century Malacca) arose as a result of trade with China and India in the 16th and 17th centuries. As ships had to sail before the winds at that time, they were totally dependent on the regular seasons of monsoons. From April to September the Southwest Monsoon (blowing from the south west) brought merchants from the west; India, Arabia, Persia and points west. Malacca became an entrepôt, with the merchants from the west bringing in their silks, jewels, textiles and glass to exchange with traders from the east. While the trading was in progress, the merchants had to remain in port, waiting for the opposite winds to carry them home. Sometimes the seafarers remained in port for up to four or five months allowing them to forge liaisons and marriages with the local Malay ladies. With the arrival of the Northeast Monsoon (from the north east) in October to March the Indian traders would depart for home and the Chinese traders would arrive with their tea, silk, porcelain and lacquered goods. The pattern was repeated with the merchants from the east, making their exchanges, then waiting for the change in winds once again. This also led to further cross-cultural blending with the women of Malacca. The Peranakan culture developed; families with a local Malay wife and a Chinese, Indian or Arab husband.

The Peranakans (people born locally of mixed heritage, usually Chinese and Malay, who can trace their origins back to 15th-century Malacca) arose as a result of trade with China and India in the 16th and 17th centuries. As ships had to sail before the winds at that time, they were totally dependent on the regular seasons of monsoons. From April to September the Southwest Monsoon (blowing from the south west) brought merchants from the west; India, Arabia, Persia and points west. Malacca became an entrepôt, with the merchants from the west bringing in their silks, jewels, textiles and glass to exchange with traders from the east. While the trading was in progress, the merchants had to remain in port, waiting for the opposite winds to carry them home. Sometimes the seafarers remained in port for up to four or five months allowing them to forge liaisons and marriages with the local Malay ladies. With the arrival of the Northeast Monsoon (from the north east) in October to March the Indian traders would depart for home and the Chinese traders would arrive with their tea, silk, porcelain and lacquered goods. The pattern was repeated with the merchants from the east, making their exchanges, then waiting for the change in winds once again. This also led to further cross-cultural blending with the women of Malacca. The Peranakan culture developed; families with a local Malay wife and a Chinese, Indian or Arab husband.

Each piece of jewelry was commissioned by the owner, so that every piece was original. The artisan would come to the home of the Nyonya lady and she would indicate what she wanted. The craftsman would come to her house daily to work on her piece, leaving the gold there overnight. Or if he did the work at his shop the lady would come at the end of the day to take the work in progress home, returning with it the next day. No room for fiddling with the gold.

The motifs and designs were generally from flora and fauna and sometimes reflected an aspect of the culture of the owner. Symbols representing long life, prosperity and family lineage or a bunch of grapes were popular among the Chinese. Local birds and insects or baskets of flowers, were intertwined and frequently cleverly hidden in the creation. Stars, the crescent and star or Jawi calligraphy were frequently favored by the Muslims, while ribbon motifs were seen as Western.

The kerongsang was in a special class of its own. Versions of most of the other pieces of jewelry are found in many cultures, but the kerongsang is unique to the Peranakans and the Malays. The ladies wore long sleeved, sheer blouses (kebaya) with the two sides meeting in the center, but there were no buttons. A system of three brooches joined by a chain, known as kerongsang was used to close the blouse, to pin the sides together running down the center of the kebaya. The top piece was usually quite elaborate and larger than the other two and was known as the ibu (mother). The next lower two being smaller were known as the anak (child), but had motifs linking them to the ibu. Taking pride of place in the center of the garment the kerongsang was the best piece to show off ostentatious wealth. Elaborate sets were decorated with intan or berlian or a combination of both or colored gem stones. The ibu was in the shape of a paisley with the point towards the heart, crowned by a large circle and two arms radiating out towards the sides, all sporting diamonds. The anak anak were smaller circles. More modest pieces were also used in which the three brooches were all the same. For instance, designs could have three sheaves of padi, three leaves, three dragon flies or three geometric designs with the advent of art deco.

Anklets also reflected motifs from nature with the ends being shaped like lotus buds and the rest resembling rope. Although made of gold, they were hollow and featured a screw device for closure. Decorative belts were worn daily too. Men were not similarly adorned, usually only wearing a single piece, with rings being most common. Muslim men wore buttons to close the neckline of their baju melayu worn for prayers or special occasions, but they were not usually gold as it is not seen as appropriate.

Our visit was informative and we certainly did learn a lot about Malaysia’s jewelry heritage. The museum is free and open to all, at 10:00 am to 5:00, Tuesday to Sunday. Along with the jewelry display there is an art gallery with rotating displays and a cozy coffee shop. Situated in Ampang Point, it is on the first floor above Habib II, between AgroBank and Cash Converters.

Leslie Muri