BG 2 – February 2023

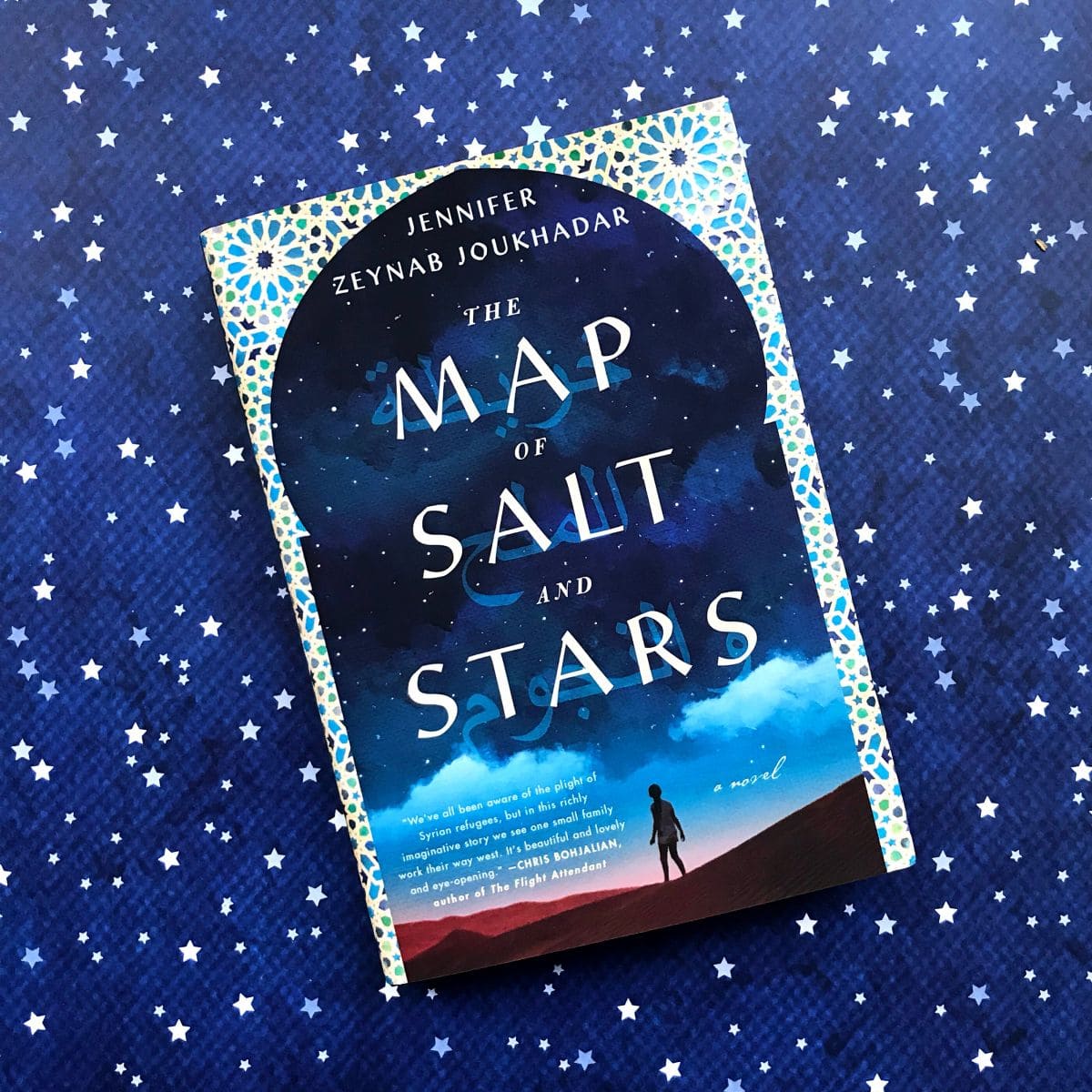

REVIEW – THE MAP OF SALT AND STARS BY JENNIFER ZEYNAB JOUKHADAR

The Map of Salt and Stars, a novel by Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar, puts a face on the tragedy of the Syrian refugee crisis. The war in Syria has raged for more than eight years now, obliterating cities and homes and casting the people who lived there adrift to seek lives elsewhere. The reader experiences it through the eyes of one of the main characters, Nour. Nour's family is Syrian, but she was born and raised in the United States.

After Nour's father dies of cancer, her family leaves New York City, the only place Nour knows well, and returns to Syria, a country she feels both is and is not her own. The strongest connection she holds to it is through history and story. All her life, her father told her stories, weaving them out of legends, history and his own creations, and they became a lens through which Nour could see the world.

One of Nour’s favourite stories is about a young, adventurous girl named Rawiya, who journeyed with famed mapmaker Al-Idrisi on his voyages and explorations in the effort to make one of history’s most famous maps: the Tabula Rogeriana. Though Al-Idrisi is a real historical figure, Rawiya is a character of Joukhadar’s creation. But Rawiya and her adventures seem so real to Nour that she begins to believe that maybe they are.

History, myth, and magic play a large role in the novel. In addition to her father’s mythical stories, Nour has synesthesia, and sees colours whenever she hears sounds. She also begins to see accumulations of salt. The salt may be a kind of magical yet tangible sublimated sorrow. After Nour’s father died, her mother refused to speak about her grief, and instead, according to Nour, “her tears watered everything in the apartment. That winter I found salt everywhere.”

Rawiya’s story unfolds alongside Nour’s in alternating chapters, giving us the sense that Rawiya’s story is either part of Nour’s imagination or a history so distinctly a part of Nour’s psyche, she gives it equal importance to her own. Their stories align in some ways – the vastness of Syria’s history, told through the journeys of Al-Idrisi and Rawiya is important to Nour and the heart of the novel – but there is a feeling of unfulfilled anticipation.

However, this doesn’t detract from the beauty of the novel’s prose and the importance of its historical metaphor. Joukhadar’s language has melancholy, and images so distinct that the reader can smell, taste, and touch the world of her creation. Nour describes their house in Homs, Syria:

“Inside, the walls breathe sumac and sigh out the tang of olives. Oil and fat sizzle in a pan, popping up in yellow and black bursts in my ears. The colours of voices and smells tangle in front of me like they’re projected on a screen: the peaks and curves of Huda’s pink-and-purple laugh, the brick-red ping of a kitchen timer, the green bite of baking yeast”.

The novel is filled with effortlessly stunning passages like this, a feat of writing. The most important aspect of the novel, however, is its treatment of history. Though it touches on myth and magic, many of the historical characters like Al-Idrisi are real and an integral part of, not only world history, but Nour’s cultural sense of self. The major message of this book is that the destruction of a homeland threatens to destroy history, but that history can never die, as long as people, like Nour, choose to remember.

This moving, debut novel places today’s headlines in the sweep of history, where the pain of exile and the triumph of courage echo repeatedly.

The group rated the book 7/10.

Nabila Ahmad